Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: What the Patient Needs to Know

Overview

A subarachnoid hemorrhage is a life-threatening condition defined as bleeding into the space around your brain. This is most commonly caused by traumatic brain injury or a ruptured brain aneurysm. The hallmark symptom of a subarachnoid hemorrhage is the sudden onset of a severe headache, often accompanied with nausea, vomiting, and a loss of consciousness.

Treatment options for subarachnoid hemorrhage include surgery (including an endovascular procedure like an angiogram) to stop the bleeding from a ruptured aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation and medications to control pain and prevent vasospasm (clamping down of the brain blood vessels). Unfortunately, only up to a third of patients survive without neurological deficits.

What Is a Subarachnoid Hemorrhage?

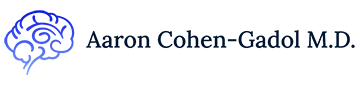

A subarachnoid hemorrhage is a life-threatening condition where bleeding occurs in the space around your brain. This blood accumulates under the arachnoid layer of the membranous covering of the brain (meninges), giving this condition its name.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage can be caused by rupture of an aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation, or traumatic brain injury. At the area of vessel rupture, blood leaks into the subarachnoid space and repeated hemorrhages/bleedings are possible. Thus, a subarachnoid hemorrhage is also a type of stroke and must be treated as soon as possible.

Although bleeding control and restoration of normal blood flow will be of utmost priority, other problems can arise from a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Normally, the subarachnoid space is filled with clear cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that is continuously produced to cushion and protect the brain. Bleeding into this space can block the normal flow of CSF. CSF accumulation within the brain leads to increased intracranial pressure in a condition known as hydrocephalus.

A few days after subarachnoid hemorrhage, red blood cells are broken down and release substances that irritate the lining of blood vessels, causing it to contract and spasm (vasospasm). This contraction narrows the diameter of previously healthy blood vessels and impedes the passage of oxygen to other regions of the brain. Delaying treatment for a subarachnoid hemorrhage and vasospasm can cause permanent brain damage, coma, and even death.

Why should you have your surgery with Dr. Cohen?

Dr. Cohen

- 7,000+ specialized surgeries performed by your chosen surgeon

- More personalized care

- Extensive experience = higher success rate and quicker recovery times

Major Health Centers

- No control over choosing the surgeon caring for you

- One-size-fits-all care

- Less specialization

For more reasons, please click here.

Figure 1. Different types of intracranial hemorrhage. In subarachnoid hemorrhage, blood accumulates in the space surrounding the brain after aneurysm rupture. This is different than hemorrhage or bleeding on the brain (subdural or epidural hematoma) and within the brain (intracerebral hemorrhage/hematoma).

What Are the Symptoms?

The classic symptom of a subarachnoid hemorrhage is a sudden and severe “thunderclap” headache, commonly described as “the worst headache of my life”. Other symptoms can include:

- Loss of consciousness

- Confusion and difficulty concentrating

- Seizures

- Nausea or vomiting

- Difficulty speaking

- Muscle aches (especially neck and shoulder)

- Neck stiffness

- Numbness

- Light sensitivity

- Blurred or Double Vision

- Drooping eyelid

What Are the Causes?

Subarachnoid hemorrhage can result from both traumatic and non-traumatic causes. In non-traumatic cases, subarachnoid hemorrhage is most often due to a brain aneurysm rupture. Bleeding can also be caused by an arteriovenous malformation, the use of blood thinners, or other bleeding disorders.

How Common Is It?

Trauma is the most common cause of subarachnoid hemorrhage. In non-traumatic cases, ruptured aneurysms are the major cause and account for 85% of patients. In the United States, the incidence of subarachnoid hemorrhage is approximately 10-14 per 100,000 population. A subarachnoid hemorrhage can occur at any age but is more common among individuals aged 40 to 65 years old. The incidence for subarachnoid hemorrhage is higher for women than men.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage risk factors include unruptured aneurysms, high blood pressure, history of polycystic kidney disease, connective tissue and autoimmune disorders, smoking, and the use of illicit drugs.

How Is It Diagnosed?

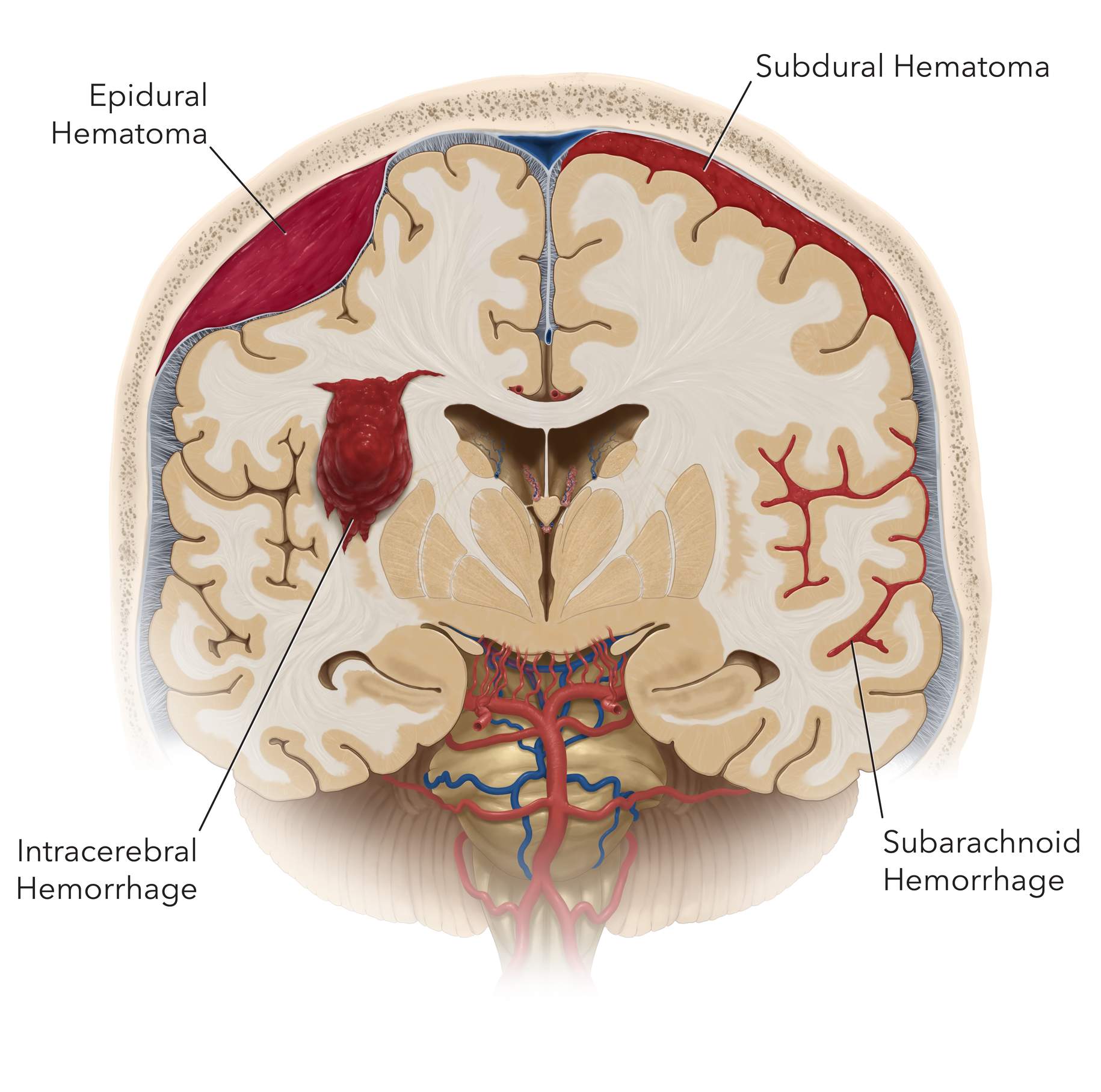

Subarachnoid hemorrhage is usually diagnosed with a CT scan, then angiography to pinpoint the source of bleeding. Some aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhages are not visualized on initial imaging and must be evaluated with a lumbar puncture.

CT uses X-rays to image the brain and can identify abnormal bleeding. In CT angiography, a contrast dye is injected into the blood stream to view blood flow. CT scans are quicker to perform than MRI scans and are typically the initial imaging method of choice in the emergency setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage.

MRI uses magnetic fields and radiofrequency waves to detect bleeding in the brain. In MRI angiography, a dye may be injected into the blood stream to better visualize the blood vessels. Although there is no radiation exposure, MRI scans take a longer time to perform than a CT scan. MRIs may be used if the patient’s condition has stabilized or to provide more information when bleeding cannot be detected by CT.

Cerebral angiography involves the insertion of a thin tube (catheter) into a blood vessel. This catheter usually starts in an artery in the arm or leg, then is guided up to the brain. A cerebral angiography may be recommended if a more detailed image is required, or if the source of subarachnoid hemorrhage is not apparent on other modes of imaging.

In a lumbar puncture, a needle is inserted into your lower back and spinal canal. Cerebrospinal fluid can be collected and analyzed for the abnormal presence of blood.

Figure 2. CT scan of a subarachnoid hemorrhage with a typical “star sign” (lighter area in the center) depicting blood in the subarachnoid spaces.

What Are the Treatment Options?

A subarachnoid hemorrhage is a life-threatening emergency. The goals of treatment are to stabilize the patient’s condition, address the source of bleeding, restore normal blood flow, and prevent complications.

Medications

Patients who are on blood thinners (for example, Jantoven) will be provided medications to reverse the effects so that blood clotting can occur and help to stop the bleeding. Medications to control pain and maintain a healthy intracranial pressure will also be administered. To prevent vasospasm, a medication called nimodipine is given within a few days after symptom onset.

Surgery

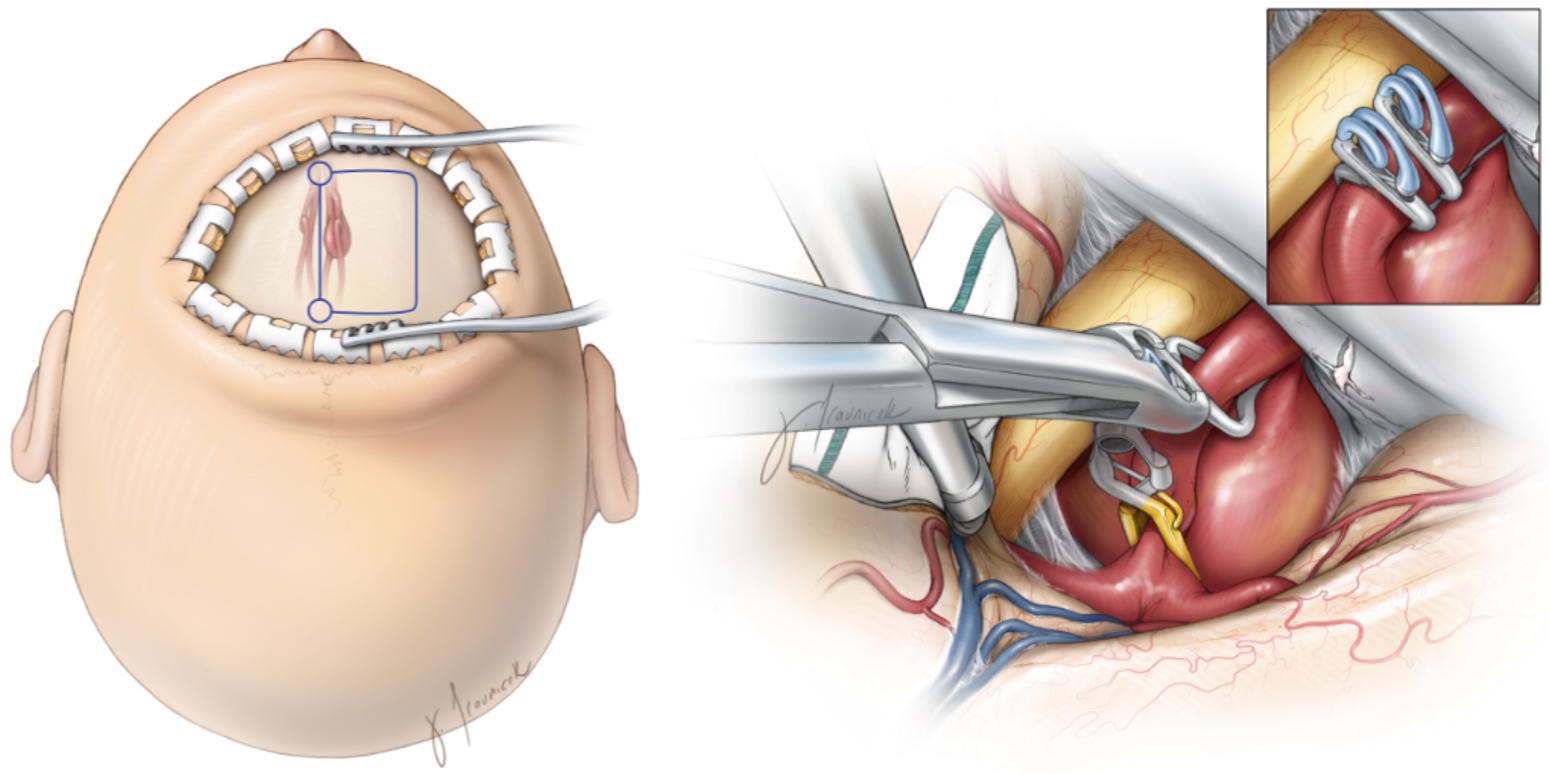

If subarachnoid hemorrhage is caused by rupture of an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation, surgery (for arteriovenous malformations) or endovascular therapy (for aneurysms) may be required to avoid another episode of bleeding.

For aneurysms, specific surgical options include microsurgical clipping or minimally invasive endovascular coiling. For arteriovenous malformations, the surgeon will remove the vascular abnormality and close off the bleeding vessels via a surgical procedure. More information on treatments can be found on the aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation pages.

Figure 3. Surgical approach and craniotomy incision outlined in blue (left), and surgical clipping of a giant aneurysm (right).

What Is the Recovery Outlook?

Outcomes for patients with subarachnoid hemorrhages vary depending on the location and severity of the initial event and the degree of neurological injury. Unfortunately, approximately 10-15% of patients who develop a subarachnoid hemorrhage die before reaching the hospital, and 25% of patients die within 24 hours.

While improvements in patient treatment are continuously developing, approximately a third of survivors live with impaired brain function. Even for patients who are considered to have good outcomes, many may still experience cognitive deficits. Working with doctors and rehabilitation therapists can help to improve recovery.

Please refer to our aneurysm and arteriovenous malformation chapters for more information about their treatment and recovery.

Resources

Glossary

Arachnoid—the delicate middle layer of the covering of the brain and spinal cord (meninges)

Catheter—thin, hollow, and flexible tube

Cerebrospinal fluid—clear fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord

Craniotomy—a procedure to open and remove a piece of bone from the skull to expose the brain

Hemorrhage—bleeding from a blood vessel

Hydrocephalus—abnormal accumulation of fluid within the brain

Meninges—three membranous layers (dura, arachnoid, pia) that cover the brain and spinal cord

Seizure—sudden burst of abnormal electrical activity in the brain that leads to uncontrollable spasms, twitching, or jerking

Stroke—a condition that occurs when blood supply to a part of the brain is interrupted or reduced which prevents the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to brain tissues

Subarachnoid space—space beneath the arachnoid membrane that usually consists of cerebrospinal fluid and blood vessels

Vasospasm—persistent contraction and narrowing of a blood vessel

Ventricles—network of cavities within the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid

Contributors: Andie Conching BA, Gina Watanabe BS

References

- Marcolini E, Hine J. Approach to the Diagnosis and Management of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(2):203-211. doi:10.5811/westjem.2019.1.37352

- Hemphill JC, Greenberg SM, Anderson CS, et al. Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2015;46(7):2032-2060. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000069

- Lawton MT, Vates GE. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Solomon CG, ed. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(3):257-266. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1605827