Brain Aneurysm: What the Patient Needs to Know

Visit our current video conferences involving aneurysms and vascular disorders

- New Endovascular Options for Brain Aneurysms: Flow Diverters

- Commonly Asked Questions in the Management of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms

- Differential Diagnosis of One’s Worst Headache

- Unveiling the Mysteries of Brain Aneurysm Treatment: Coil and Clip

- Mood and Sleep Disorders Associated With Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

- Rehabilitation After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: How Can We Accelerate Recovery?

- Brain Aneurysms and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: What the Caregivers Need to Know

- Brain Aneurysm and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: An Open Forum of Questions and Answers

- Advances in Vascular Microsurgery: Application of Fluorescence Video Angiography

- Anterior Communicating Artery Aneurysm

General Aneurysm Information

Overview

A brain aneurysm is a small balloon-like swelling on the wall of one or more blood vessels supplying the brain. Symptoms usually do not occur until the aneurysm ruptures. Patients then experience an acute onset of severe headache, often described as “the worst headache of my life.” A person suspected of experiencing a brain aneurysm rupture should seek immediate medical attention. Treatment options include surgery, an endovascular procedure, or, for a small unruptured aneurysm, observation.

Why should you have your surgery with Dr. Cohen?

Dr. Cohen

- 7,000+ specialized surgeries performed by your chosen surgeon

- More personalized care

- Extensive experience = higher success rate and quicker recovery times

Major Health Centers

- No control over choosing the surgeon caring for you

- One-size-fits-all care

- Less specialization

For more reasons, please click here.

What Is an Aneurysm?

A brain aneurysm is a small balloon-like swelling on the wall of one or more blood vessels supplying the brain. It is a result of weakening in the wall of the blood vessel. This bulge is filled with blood and can cause neurological symptoms upon rupture or by pressing on nearby nerves and brain tissue. Brain aneurysms can also be called cerebral or intracranial aneurysms.

Difference Between a Ruptured and Unruptured Brain Aneurysm

A ruptured brain aneurysm occurs when an aneurysm bursts, causing blood to spread into the space surrounding the brain. This bleeding, called subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), can result in severe complications such as hemorrhagic stroke. Both SAH and hemorrhagic stroke are potentially life-threatening.

Meanwhile, an unruptured brain aneurysm has not yet burst. However, unruptured aneurysms may burst at any time.

To summarize, the primary difference between an unruptured and a ruptured aneurysm lies in whether the aneurysm remains intact or has burst and bled. This distinction is an important factor impacting the type and severity of the patient’s symptoms, the possible complications, and the proposed treatments.

Types of Brain Aneurysms

Brain aneurysms vary in location and type. Most of them occur at an arterial branch point and are located below the brain and at the base of the skull.

There are 4 major types of aneurysms:

- Saccular aneurysms, the most common type, bulge from one side of an artery

- Giant aneurysms are over 2.5 cm wide and can involve multiple arteries

- Fusiform aneurysms bulge from all sides of an artery

- Mycotic aneurysms are relatively rare and are caused by an infected arterial wall

What Are the Symptoms?

Aneurysms can cause symptoms by pressing on nearby nerves and brain tissue. Pain above and behind the eye, numbness, weakness, and/or vision changes are some brain aneurysm symptoms that have been reported.

However, most patients do not experience symptoms until the aneurysm ruptures. This rupture causes bleeding into the subarachnoid space surrounding the brain (subarachnoid hemorrhage).

Patients experience an acute onset of severe headache, often described as “the worst headache of my life.” A person suspected of having a brain hemorrhage should seek immediate medical attention.

Other symptoms of a ruptured aneurysm can include:

- Brief blackout

- Nausea and vomiting

- Vision problems

- Speech problems

- Confusion or sluggishness

- Paralysis or weakness on one side of the body

- Seizures

- Clumsiness

- Sudden changes in cognitive functioning or mood

- Coma

Blood released from an aneurysm rupture can directly damage brain cells, resulting in a variety of neurological deficits depending on the location of the blood in the brain. Bleeding can also increase the pressure inside the head.

The blood can prevent the flow and absorption of normal cerebrospinal fluid around and inside the cavities (ventricles) of the brain, resulting in enlarged ventricles and a condition known as hydrocephalus. Hydrocephalus is associated with symptoms such as drowsiness and confusion.

When the blood from a ruptured aneurysm meets the surrounding arteries supplying the brain, it can cause a condition known as vasospasm. The affected artery constricts in response to the leaked blood, which reduces the transport of oxygen to brain tissues and can cause stroke and brain damage. Vasospasm is often a delayed response to aneurysm bleeding and usually occurs after 3 days and up to 2 weeks after the initial bleed.

What Are the Causes?

Little is currently known about the exact cause of aneurysms. However, while brain aneurysm causes often remain unknown, there are several risk factors associated with aneurysm development.

These may include:

- High blood pressure

- Smoking

- Family history of brain aneurysm

- Cocaine abuse

- Excessive alcohol use

- Brain arteriovenous malformation

- Certain genetic conditions such as:

- Autosomal polycystic kidney disease

- Fibromuscular dysplasia

- Marfan syndrome

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV

How Common Is It?

Anyone can develop a brain aneurysm. Approximately 1% to 5% of the adult population may have a brain aneurysm. Most aneurysms are small and do not rupture during the patient’s lifetime. However, a ruptured aneurysm is seen in approximately 10 of every 100,000 people annually in the United States. Risk factors for aneurysm formation and rupture include high blood pressure and smoking. Large aneurysms are more prone to rupture than smaller ones.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Your doctor can order several different types of tests if you are suspected of having a cerebral aneurysm or aneurysm rupture. Common tests include:

- A computed tomography (CT) scan

- Arteriography/angiography

- A spinal tap

A CT scan can be ordered to look for the possibility of blood leaked around and/or into the brain. It is a series of x-ray images compiled by a computer. When a contrast dye is injected into a vein, a CT scan can also show vasculature.

Arteriography is frequently done to image the arteries in the brain and look for an aneurysm. A catheter is guided through the groin or forearm and via the arteries into the neck, where a contrast dye is released into the brain’s vasculature. An x-ray image is then taken to outline the blood vessels and look for an aneurysm.

A spinal tap (or lumbar puncture) is done to look for blood in the patient's cerebrospinal fluid if the CT scan is unrevealing. It is done with a needle inserted into the lower spine after the application of a local anesthetic.

What Are the Possible Complications?

As mentioned previously, a ruptured aneurysm could result in serious complications. Apart from SAH and hemorrhagic stroke, potential complications of a ruptured aneurysm include the following:

- Vasospasm - This occurs when the blood vessels in the brain contract. Vasospasm could restrict blood flow, which in turn may cause additional damage to brain cells and result in strokes.

- Hydrocephalus - Bleeding in the brain can cause a buildup of too much cerebrospinal fluid in the brain. This puts excessive pressure on the brain, potentially resulting in permanent brain damage.

- Rebleeding - A ruptured aneurysm may burst again before it is treated. This could cause more damage to brain cells.

What Are the Treatment Options?

Options for treatment vary depending on the patient’s age and condition and the aneurysm’s size, type, and location. Aneurysms that rupture and cause bleeding (no matter what size) and aneurysms that are larger than 7 mm (even if they have not ruptured) require treatment. Smaller aneurysms, especially if they are found incidentally and cause no symptoms, can be monitored over time.

If an aneurysm has not ruptured, the risk of bleeding is estimated at 0.05% per year for aneurysms smaller than 7 mm and at about 1% per year for aneurysms larger than 7 mm. Aneurysms can be treated with surgery or an endovascular procedure that does not require opening of the skull.

Observation

Small, unruptured aneurysms (less than 7 mm in diameter) are less prone to rupture and may not be treated. Instead, the aneurysm will be carefully monitored with yearly imaging to ensure that it does not grow and the risk of rupture does not increase.

Surgery

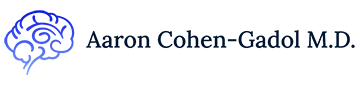

Open surgical treatment through a craniotomy involves clipping the aneurysm. Your surgeon will temporarily remove a small piece of skull and cut the outer covering of the brain, find the aneurysm, and then place a small titanium clip on the neck of the aneurysm to cut off its blood flow, which prevents any future bleeding from the aneurysm.

Figure 4. Surgical approach and craniotomy incision (outlined in blue) (left) and surgical clipping of a giant aneurysm (right).

As an alternative, the surgeon can perform a similar procedure known as an occlusion; the entire artery from which the aneurysm comes is clipped. This procedure is usually necessary when the aneurysm has damaged the blood vessel or is not amenable to other therapies.

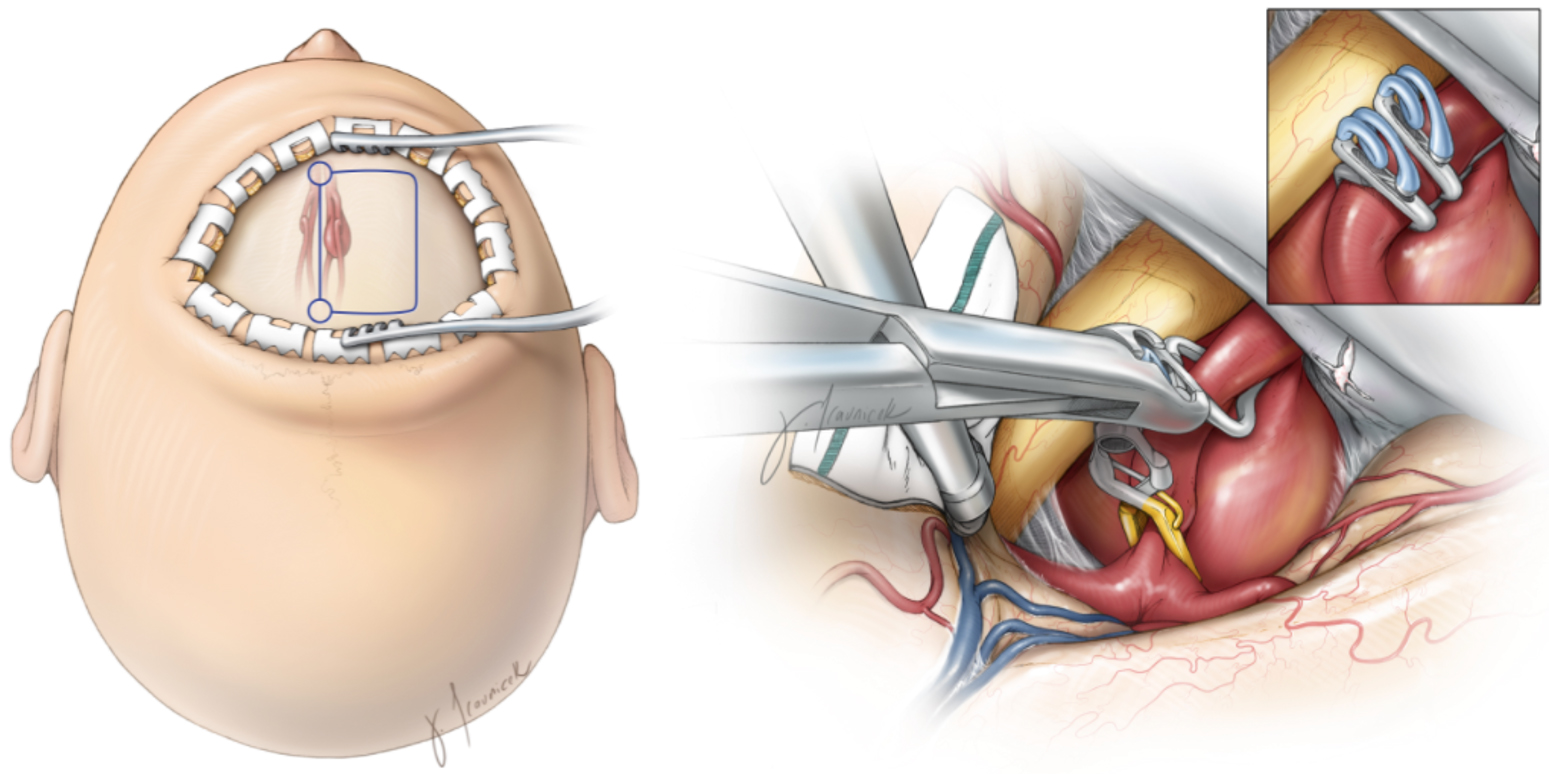

Because occlusion of an artery cuts off all blood flow through that vessel, a bypass might be performed to restore blood flow to the part of the brain fed by that artery. The bypass involves grafting a small blood vessel to the artery to reroute the flow of blood around the clipped section and past the aneurysm.

If the patient has a ruptured aneurysm, additional treatments might be necessary. A shunt or drain can be placed in the ventricles or skull to relieve the pressure of fluid accumulation from the bleeding. Appropriate drugs can be administered to prevent vasospasm or the possibility of seizures. The patient's blood pressure will be monitored and controlled through medication to prevent further bleeding.

The average hospital stay is 2 to 3 days for the treatment of an unruptured aneurysm and at least 9 to 18 days for the treatment of a ruptured aneurysm. Patients are monitored for any signs of neurological change. Antiseizure medications might be administered after surgery. Patients should avoid heavy physical activity for at least 6 weeks and discuss with their surgeon when they can return to activities such as driving.

Patients who have experienced a brain hemorrhage often receive cognitive, occupational, and physical therapy to cope with any remaining neurological and physical deficits. Rehabilitation can be intense, requiring 6 months to 1 year of therapy. The rehabilitation period is lengthy, and the patient and his or her family members must be patient and understanding. Family support services are of critical importance.

In this video, Dr. Cohen describes the techniques for surgery to treat an anterior choroidal artery aneurysm.

For more information about the technical aspects of the surgery and extensive experience of Dr. Cohen, please refer to the chapter on Anterior Choroidal Artery Aneurysm in the Neurosurgical Atlas.

In this video, Dr. Cohen describes the techniques for clip ligation to treat recurrent and remnant aneurysms after coiling.

For more information about the technical aspects of the surgery and extensive experience of Dr. Cohen, please refer to the chapter on Clip Ligation of Previously Coiled Aneurysm in the Neurosurgical Atlas.

Endovascular Procedure

Endovascular procedures avoid the need for directly opening the skull and are instead performed via a catheter guided through the arteries from the groin or forearm to the brain.

An interventional neuroradiologist or neurosurgeon will use x-rays to navigate the catheter into the affected artery to release either coils of platinum wire or similar materials into the aneurysm. The coils block off the aneurysm. Over time, a blood clot forms to effectively seal off the aneurysm.

What Is the Recovery Outlook?

Surgery or the endovascular procedure can completely obliterate the aneurysm in most patients. In rare cases, aneurysms can recur.

Depending on other health conditions and the type of treatment used, patients may be monitored every 2 to 5 years to ensure that the aneurysm has not recurred.

Recovery can take 6 to 12 weeks or longer. If neurological and physical deficits exist, a supportive rehabilitation team can help to improve long-term recovery.

Resources

Glossary

Arachnoid—delicate middle layer of the covering the brain and spinal cord (meninges)

Catheter—thin, hollow, flexible tube

Cerebrospinal fluid—clear fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord

Craniotomy—procedure to open and remove a piece of bone from the skull to expose the brain

Hemorrhage—bleeding from a blood vessel

Hydrocephalus—accumulation of fluid within the brain

Meninges—three membranous layers (dura, arachnoid, pia) that cover the brain and spinal cord

Stroke—condition that occurs when blood supply to a part of the brain is interrupted or reduced, which prevents the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to brain tissues

Subarachnoid space—space beneath the arachnoid membrane that usually consists of cerebrospinal fluid and blood vessels

Vasospasm—persistent contraction and narrowing of a blood vessel

Ventricles—network of cavities within the brain filled with cerebrospinal fluid

Contributor: Gina Watanabe BS

References

Brisman JL, Song JK, Newell DW. Cerebral aneurysms. N Eng J Med 2006;355:928–939. doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra052760

Britz GW, Salem L, Newell DW, et al. Impact of surgical clipping on survival in unruptured and ruptured cerebral aneurysms. Stroke 2004;35:1399–1403. doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000128706.41021.01

Pierot L, Wakhloo AK. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms. Stroke 2013;44:2046–2054. doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.000733