Overview of Acoustic Neuroma

Overview

An acoustic neuroma, or vestibular schwannoma, is a tumor that arises from the covering of the nerve responsible for hearing and balance as it passes from the inner ear to your brain. These tumors are noncancerous and generally grow slowly.

Thus, small acoustic neuromas might not require treatment. With larger tumors, patients might experience hearing loss, tinnitus or ringing in the ear, and unsteadiness or balance problems. Treatment options for acoustic neuroma include observation, surgical removal, and radiation.

What Is an Acoustic Neuroma?

An acoustic neuroma, also called vestibular schwannoma, is a noncancerous and generally slow-growing tumor that arises from the Schwann cell covering of the vestibulocochlear nerve. This nerve is responsible for hearing and balance as it passes from the inner ear to your brain.

The tumor expands from the bony auditory canal and into the base of the skull, forming a distinctive pear-shaped tumor. While it does not typically infiltrate and invade the brain, it might push on other nerves or the brainstem, resulting in symptoms.

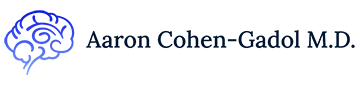

Figure 1: MRI of a patient’s brain with a large acoustic neuroma (left) and a drawing of a large acoustic neuroma pressing on surrounding brain structures (right).

Types of Acoustic Neuromas

Acoustic neuromas are primarily classified based on their size and location, which also influence the treatment choice of the patient. They can be categorized as:

- Intracanalicular Acoustic Neuromas: These are small tumors confined to the internal auditory canal, the narrow passageway from the inner ear to the brain. They typically affect hearing but may have fewer symptoms related to balance or facial nerve function due to their limited size and location.

- Extracanalicular Acoustic Neuromas: These tumors extend beyond the internal auditory canal into the cerebellopontine angle, where the cerebellum, pons, and medulla parts of the brain are located. This type tends to be larger and can affect hearing, balance, and facial nerve function due to its broader impact on surrounding neural structures.

Why should you have your surgery with Dr. Cohen?

Dr. Cohen

- 7,000+ specialized surgeries performed by your chosen surgeon

- More personalized care

- Extensive experience = higher success rate and quicker recovery times

Major Health Centers

- No control over choosing the surgeon caring for you

- One-size-fits-all care

- Less specialization

For more reasons, please click here.

Are Acoustic Neuromas Dangerous?

While acoustic neuromas are benign and do not metastasize like malignant tumors, they can still pose significant risks if they grow large enough. The primary danger of an untreated or rapidly growing acoustic neuroma is its potential to compress adjacent cranial nerves, the brainstem, or even the cerebellum.

Such compression can lead to a range of neurological deficits, including hearing loss, balance disorders, facial paralysis, or more severe symptoms like headaches, nausea, and, in extreme cases, life-threatening conditions due to pressure on the brain and/or brainstem.

What Are the Symptoms?

Acoustic neuromas often cause no symptoms at all, especially if the tumor is small. Larger tumors, however, can compress structures around them and cause symptoms such as hearing loss, tinnitus or ringing in the ear, and unsteadiness or balance problems.

The earliest symptom seen in 90% of patients is a reduction in hearing on the side with the tumor (sometimes especially noticeable when speaking on the phone) that can be mistaken for normal changes that come with age.

If the facial nerve neighboring the vestibulocochlear nerve becomes involved, there can be weakness of the facial muscles, which makes it difficult to blink or smile. In addition, the increase in pressure inside the head can lead to headache, weakness, and confusion.

In extreme cases, a large tumor can compress the trigeminal nerve (which provides sensation to the face), resulting in facial numbness. Such large tumors can also invade the brainstem, where vital functions such as breathing and heart rate are coordinated.

What Are the Causes?

In most cases, there is no well-defined cause of acoustic neuromas. Some studies have linked such tumors with prolonged exposure to loud noise, but this link has not been confirmed. There might also be a link to radiation exposure over one’s lifetime.

In a small number of cases, acoustic neuromas are part of a rare genetic condition called neurofibromatosis type 2, caused by a malfunctioning gene on chromosome 22. Such cases would usually involve acoustic tumors on both sides of the head.

How Common Is It?

Recent reports stated that acoustic neuromas are becoming more common, but this phenomenon might be due to advances in imaging that enable physicians to detect more tumors earlier than ever.

Current estimates indicate that acoustic neuromas occur in about 2 in every 100,000 people. They are diagnosed most commonly in patients who are between 30 and 60 years old.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Acoustic neuromas are diagnosed by a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain. This test is often performed with a contrast material, gadolinium, that helps to define the tumor precisely.

An audiogram should be performed along with MRI to test hearing function in both ears. Finally, some patients might undergo an auditory brainstem response test.

This test measures electrical impulses along the nerve to the brain. A defect in conduction through this nerve might suggest the presence of a tumor.

What Are the Treatment Options?

Acoustic neuroma treatment varies depending on several factors, including your overall health and tumor size. There are currently 3 main acoustic neuroma treatment options from which patients and physicians can choose:

- Observation

- Surgery

- Radiation

Observation

The most conservative approach to an acoustic neuroma is observation. Because these tumors are not cancerous and grow very slowly, some patients choose to simply follow the tumor over a period of time if they are older or have very a small tumor that was discovered incidentally. If this option is chosen, the patient must undergo an MRI scan on a yearly basis for at least 5 years to make sure that the tumor is not growing.

Surgery

Surgery for an acoustic neuroma is good for patients with a larger tumor that is pushing on the brainstem. This method can remove the tumor either completely or partially, depending on the decision reached by the surgeon and the patient.

Partial removal will decrease the tumor’s size and reduce or eliminate any symptoms associated with it. This option, however, requires the patient to undergo regular MRI follow-up to ensure that the tumor is not growing.

Complete removal of the tumor is possible and preferable in many cases. In attempting complete removal, the goal of the surgeon is to preserve both the facial and hearing nerves. Both nerves are electrically monitored during the entire surgery, and the surgeon is alerted immediately if any defect is detected.

After surgery, most patients are in the hospital for 3 to 5 days and have 4 to 6 weeks of at-home recovery. Many patients do not need this much time to reach the same level of wellness they had before the surgery.

There are currently 3 surgical approaches, and the patient and physician should discuss which of them is best to follow:

- Translabyrinthine—this approach is used when hearing preservation is not required (that is, when the patient has already lost hearing in the affected ear). The incision is located behind the ear, and the surgeon drills through the mastoid bone, exposing the tumor from below.

This approach allows the surgeon to see the facial nerve early and ensure its preservation. In this procedure, a small amount of fat is taken from the abdomen and used to pack the surgical area to prevent any leakage of brain fluid (cerebrospinal fluid) after surgery.

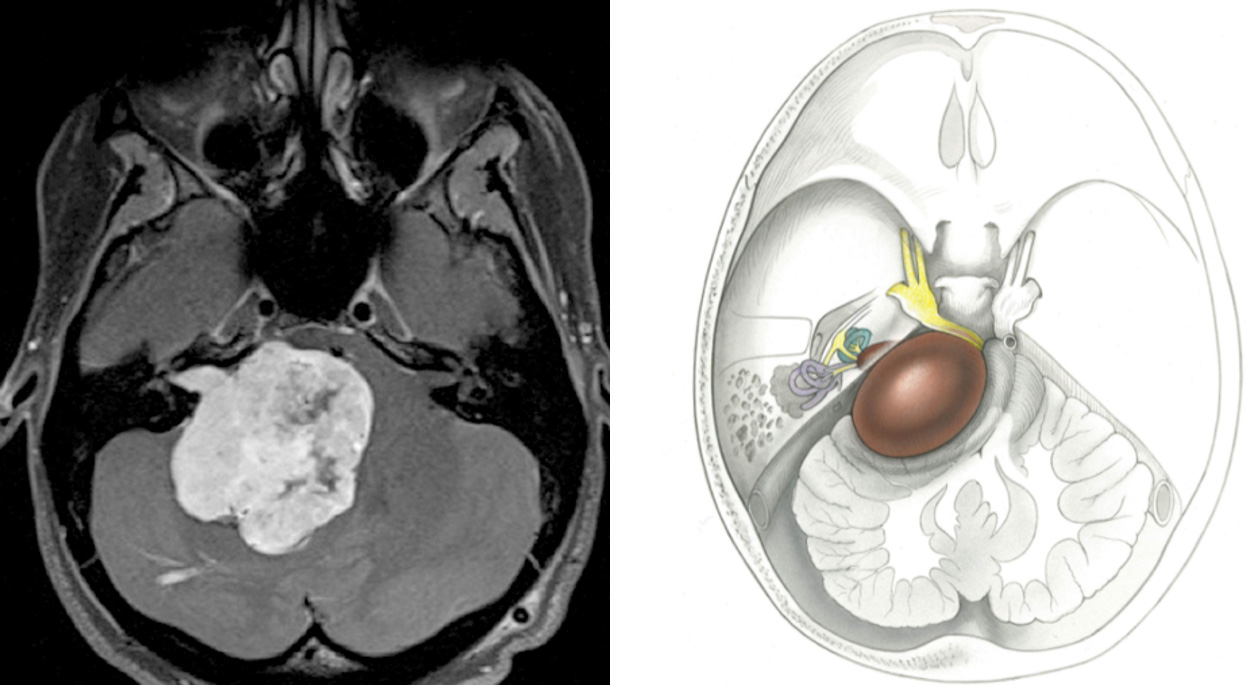

- Retrosigmoid or suboccipital—this approach is used when hearing preservation is a major goal or it is the surgeon’s preference. The incision is several centimeters behind the ear, and the tumor is exposed from its back side. This approach also enables identification and preservation of the facial nerve.

- Middle fossa—this approach is also used to preserve hearing. The incision is on the top part of the head, a few centimeters above the ear, and provides exposure of the tumor from the top.

In this video, Dr. Cohen describes the resection of an acoustic neuroma using the translabyrinthine approach.

For more information about the technical aspects of the surgery and extensive experience of Dr. Cohen, please refer to the chapter on Surgery for Acoustic Neuroma: Translabyrinthine Approach in the Neurosurgical Atlas.

In this video, Dr. Cohen demonstrates the resection of an intracanalicular acoustic neuroma using the retrosigmoid approach.

For more information about the technical aspects of the surgery and extensive experience of Dr. Cohen, please refer to the chapter on Surgery for Acoustic Neuroma: Retrosigmoid Approach in the Neurosurgical Atlas.

Figure 2: Removal of an acoustic neuroma via the retrosigmoid approach involves making a cut behind the ear (left) and carefully peeling the tumor off of the vestibulocochlear nerve (right).

Possible complications of acoustic neuroma surgery include infection, leak of cerebrospinal fluid out of the nose or incision site, stroke, hearing loss, temporary paralysis of the face muscles, dizziness or vertigo, and headaches. One might also experience eye dryness, which can be treated with eye drops.

Hearing loss, paralysis of the facial muscles, and tinnitus or ringing in the ear might occur because of the manipulation of these nerves during surgery.

Although these symptoms are most often temporary, depending on the extent of damage to these nerves and the amount of involvement of the nerves with the tumor, these side effects can become permanent.

Most patients experience vertigo, or a feeling of the room spinning around them, for about 1 week or more after the surgery. Headaches are also a common complaint after surgery.

These symptoms will pass within a few weeks, but a small number of patients might experience them on a chronic basis; these patients can be treated with a variety of medications to relieve their discomfort. The occurrence of these complications is lowest with smaller tumors.

Radiation

Radiation is another treatment option for acoustic neuromas. There are 2 ways to deliver this treatment. One way is radiosurgery, which involves one large dose of radiation delivered to the tumor.

The other way is fractionated radiotherapy, in which multiple small doses of radiation are delivered over a period of several weeks. This procedure is noninvasive and requires no hospital stay for recovery.

In radiosurgery, hundreds of small, concentrated beams of radiation are aimed at the tumor using 1 of the 3 currently available radiosurgical devices (Gamma Knife, Cyber Knife, or Novalis). The procedure itself takes 30 to 50 minutes, and the patient is placed in a stereotactic headframe on the day of the procedure, which stabilizes the head and allows the treatment team to calibrate the machine to the patient’s head and tumor.

The patients who undergo fractionated radiotherapy receive smaller doses of radiation over several visits. Each visit takes only 5 to 15 minutes, and the patient is able to go about his or her business before and after the visit. Fractionated radiotherapy poses less risk to the facial and hearing nerves.

It is important to note that radiation therapy does not remove the tumor. It might, in some cases, cause the tumor to shrink. The main goal of radiation is to stop the tumor from growing. As a result, the patient must return for an MRI scan every year to check for any new growth.

Possible complications of radiation therapy include facial numbness and weakness, as well as hearing loss. These side effects are usually temporary and pass within several weeks of the procedure.

With fractionated radiotherapy, it might take up to 18 months for the therapy to completely stop the growth of the tumor.

However, radiation therapy is noninvasive and does not carry the risks of infection, cerebrospinal fluid leak, and stroke that are associated with surgery. Also, patients usually have no vertigo or headache after the procedure.

Possible Long-Term Complications

Regardless of the treatment method, patients may experience long-term effects such as persistent balance issues, chronic headaches, or ongoing facial nerve dysfunction. These acoustic neuroma complications can impact the quality of life and may require long-term management through physical therapy, medication, or further surgical interventions.

What Is the Recovery Outlook?

Most patients who undergo surgical removal of an acoustic neuroma experience near-complete removal of the tumor. However, in a small number of people, the tumor can reappear; it is important that such a reappearance be closely followed or treated with radiation.

After surgery or radiation, the patient should undergo regular follow-up MRI scans and appointments with her or his surgeon to ensure that the tumor does not return. Any resulting complications should be treated with medication and/or physical therapy as needed.

Resources

Glossary

Vestibulocochlear nerve—the 8th pair of cranial nerves, which consists of sensory fibers responsible for balance and hearing

Facial nerve—the 7th pair of cranial nerves, which supplies motor fibers to facial muscles

Schwann cell—cells that form an insulating cover around the length of a nerve

Cerebrospinal fluid—clear fluid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord

Tinnitus—a feeling of ringing or buzzing in one or both ears

Contributor: Gina Watanabe BS

References

- Stangerup S-E, Caye-Thomasen P, Tos M, et al. The natural history of vestibular schwannoma. Otol Neurotol 2006;27:547–552. doi.org/10.1097/01.mao.0000217356.73463.e7.

- Raftopoulos C, Abu Serieh B, Duprez T, et al. Microsurgical results with large vestibular schwannomas with preservation of facial and cochlear nerve function as the primary aim. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2005;147:697–706; discussion 706. doi.org/10.1007/s00701-005-0544-0.

- Kentala E, Pyykkö I. Clinical picture of vestibular schwannoma. Auris Nasus Larynx 2001;28:15–22. doi.org/10.1016/S0385-8146(00)00093-6.